Ultraprocessed Nation

Humans have been processing food for millenniums. Hunter-gatherers ground wild wheat to make bread; factory workers canned fruit for soldiers during the Civil War.

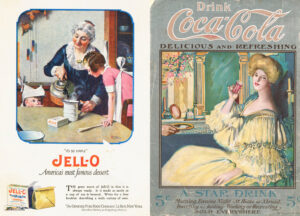

But in the late 1800s, food companies began concocting products that were wildly different from anything people could make themselves. Coca-Cola came in 1886, Jell-O in 1897, and Crisco in 1911. Spam, Velveeta, Kraft Mac & Cheese and Oreos arrived in the decades that followed. Foods like these often promised ease and convenience. Some of them filled the bellies of soldiers in World War II.

Eventually, these products overtook grocery shelves and American diets. Now they are among the greatest health threats of our time. How did we get here? Today’s newsletter is a tour through food history.

Wartime Innovation

During World War II, shelf-stable foods were developed to feed soldiers.

During World War II, companies devised shelf-stable foods for soldiers — powdered cheeses, dehydrated potatoes, canned meats and melt-resistant chocolate bars. They infused new additives like preservatives, flavorings and vitamins. And they packaged the foods in novel ways to withstand wet beach landings and days at the bottom of a rucksack.

After the war, food companies realized that they could adapt this foxhole cuisine into profitable convenience foods for the masses. Advertisements told homemakers that these products offered superior nutrition and could save them time in the kitchen. Wonder Bread commercials from the 1950s, for instance, claimed its vitamins and minerals would help children “grow bigger and stronger.” An ad for Swift’s canned hamburgers boasted that they were “out of the can and onto the bun” in minutes.

Getty Images

More women found work outside the home, and by the mid-1970s, they spent much less time cooking. But they were still expected to feed their families. Fish sticks, frozen waffles and TV dinners filled modern freezers, and convenience foods became more popular. These products weren’t all ultraprocessed — some were just whole foods that had been frozen or canned with a simple ingredient, like salt. Still, people got used to the idea that packaged goods could replace cooking from scratch.

An Explosion

By the 1970s, innovations in fertilizer, pesticide and crop development, along with farm subsidies, led to a glut of grain. Companies turned it into ingredients like high-fructose corn syrup and modified starch to fill sugary cereals, sodas and fast foods.

In the 1980s, investors wanted food manufacturers to show larger profits, so they developed thousands of new drinks and snacks and marketed them aggressively. (Have a look at how the ads changed over the last century.)

The tobacco companies Philip Morris and R.J. Reynolds diversified into the food industry, dominating it through the early 2000s. They applied the same marketing techniques that they crafted to sell cigarettes — targeting children and certain racial and ethnic groups. Kraft, owned by Philip Morris, created Kool-Aid flavors for the Hispanic market and handed out coupons and samples at cultural events for Black Americans.

Obesity tripled in children and doubled in adults between the mid-1970s and the early 2000s.

A Health Crisis

Getty Images

By the 21st century, you couldn’t walk through a school cafeteria, a supermarket or an airport without being inundated by ultraprocessed foods. Obesity kept rising, and food companies addressed it by making products they marketed as “healthier,” like low-carb breakfast cereals, shakes and bagels; artificially sweetened ice creams and yogurts; and snacks like Oreos and Doritos in smaller, 100-calorie packs.

They were popular, but they did not make us healthier. Scientists soon linked ultraprocessed foods to Type 2 diabetes, cognitive decline and cardiovascular disease. For generations, obesity had been seen as a problem of willpower — caused by eating too much and exercising too little. But in the last decade, research on ultraprocessed foods has challenged that notion, suggesting that these foods may drive us to eat more.

Today, scientists, influencers, advocates and politicians publicly condemn ultraprocessed foods, which represent about 70 percent of the U.S. food supply. Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. calls them “poison.”

Are we at a tipping point? Maybe. There are signs that people are eating slightly fewer of these foods. But our reliance on ultraprocessed food was “decades in the making,” one expert told me, and “could take decades to reverse.”

|

Alice Callahan, a Times reporter, has a Ph.D. in nutrition.

|